While people tend to focus more of their attention towards the stock portion of their portfolios, but understanding the underlying fundamentals of your bond portfolio is important too.

The biggest mistakes investors make tend to occur when yields are their lowest, so listen now to learn:

- The key drivers of bond returns

- How rising rates can be a good thing for long-term investors

- The disadvantages of owning individual bonds instead of bond funds

Episode

Show Notes

While people tend to focus most of their attention towards the stock portion of their portfolios, understanding the underlying fundamentals of your bond portfolio is important too.

Yields have been exceptionally low for quite some time, and if there is one thing I’ve learned about how investors react to their bond holdings, the biggest mistakes tend to be made when yields are at their lowest.

The biggest mistakes with bonds tend to happen when yields are at their lowest.

If you’ve been questioning your own bold holdings lately, covering the basics can help you feel more confident in this part of your portfolio and also provide context to questions you might have around things like rising interest rates.

How To Measure Return on Your Bond Portfolio

The total return you receive by holding a bond until it matures is measured by yield to maturity. That is the sum of all interest payments you receive until maturity, as well as any gain or loss of principal.

For an example, consider a bond with the following characteristics:

- 10-year term

- $1,000 face value

- $80 annual interest payment

If you bought this bond at par (meaning you paid the face value of $1,000), then the yield to maturity is 8.0%. If you bought the same bond at a discount of $900, then the yield to maturity is 9.6%.

The increase in return results from buying the bond below its stated face value. This works the other way around, too. If you buy the bond at a premium of $1,100, then the yield to maturity is 6.6%. The decrease in return here results from buying the bond above its stated face value.

Bond Prices and Interest Rate Changes

Once you buy a bond, like any other asset, the price changes. With individual bonds, you might not see that change unless you are putting the holding up for bid every day, but the price and expected return of a bond is constantly changing.

Bonds experience price volatility in response to various factors, but the most prevalent is changes in market interest rates.

As market interest rates rise, the prices of outstanding bonds with lower rates fall. Conversely, as interest rates fall, prices of outstanding bonds rise until their yield matches that of new bonds issued at the current rate.

This relationship can be illustrated using a simplified yield calculation¹ that I’ll be sure to drop into the show notes, just because sometimes it’s easier to digest numbers when you’re reading them instead of listening to them.

For all of you bond experts out there, do note that this example uses current yield rather than yield-to-maturity for the sake of simplicity

Let’s say you own a $1,000 bond with an annual interest payment of $80, your current yield is 8.0% ($80 / $1000 = 8.0%). If market interest rates rise to 9.0%, your bond decreases to roughly $888 ($80 / $888 = 9.0%). If market interest rates fall to 7%, the price of your bond increases to $1142 ($80 / $1142 = 7.0%).

In real life, changes in interest rates don’t affect all bonds equally. Duration measures how sensitive a bond’s price is to changes in interest rates – and higher duration bonds experience bigger gains and losses in response to a change in interest rates.

Rising Rates

Although rising rates result in immediate bond price declines, long-term returns are actually enhanced due to the ability to reinvest at higher rates.

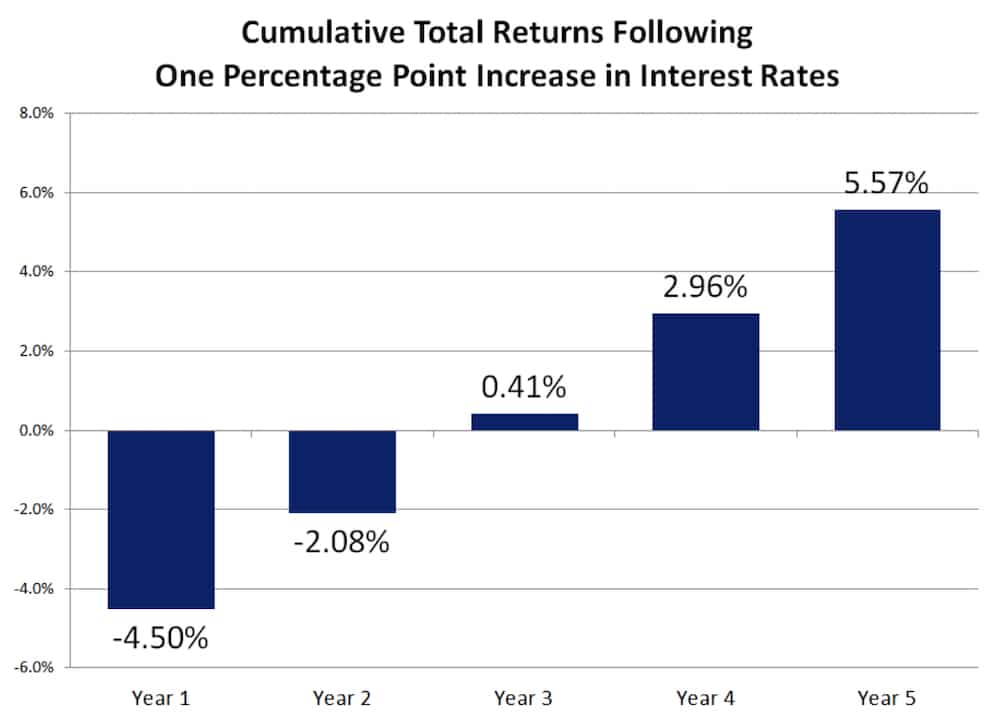

Understanding the math behind this concept is really important, but I’ve come to learn that some people have to see it visually for it to sink in, so I’ll be sure to add a chart to the show notes for the example I’m about to share.

Imagine a scenario in which there is a one time shift in yields across the entire bond market of one percentage point. In this analysis, which again you can find in the show notes on TheLongTermInvestor.com, I use a bond that has the same starting yield and duration as the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which is a total market bond index that is commonly used in the finance profession.

So 7 a one-time parallel shift in yields of one percentage point and then no further fluctuations in interest rates would result in a loss of 4.5% in Year 1, but the loss shrinks by Year 2 as interest and principal is reinvested at higher rates. By Year 3, the cumulative return turns positive and, over time, the cumulative return grows even more as the benefit of higher rates compound.

Part of that is because I’m assuming that all income received is reinvested because…

- It’s a realistic assumption

- It’s an important part of the math here because reinvesting income at higher rates helps offset the losses in the initial hike year and increases the total return of the bond portfolio over time.

The purpose of this example is to say that even though interest rates have been rising in the past year, that’s not a good reason to abandon your long-term allocation. When rates rise, bonds will eventually provide nominal returns equal to their yield over a time period equal to their duration.

The fear of rising interest rates is probably the most common question I get about bond holdings, but a close second is related to how you can earn more on your bond portfolio.

Drivers of Bond Performance: Term and Credit Risk

Fixed Income Term Risk and Return

Relative returns are largely driven by the term and credit quality of a bond.

Longer-term bonds experience bigger price movements for a given change in interest rates. As a result, investors expect to be compensated for taking that extra risk as a result.

I’ll drop a table in the show notes where you can see historical returns across different bond terms where you can see that 20+ year bonds have historically earned about half a percentage point more than 5-year bonds, but with roughly double the volatility.

This extra return being earned is referred to as the “term premium.”

Although longer-term bonds offer higher yields and returns, my opinion is that they rarely offer enough of a return premium to justify the higher risk when compared to short-term bonds.

Fixed Income Credit Risk and Return

Term is one of the major drivers of bond returns, the other is credit risk.

By loaning money to a company with lower credit quality, investors face a higher risk of not receiving all of the promised interest and principal payments. In addition, lower rated bonds tend to drop more in value when the economy slows because recessions lead to lower profits and increase the likelihood of default. Consequently, investors require a higher yield to compensate for taking the extra risk.

The relationship between fixed income credit risk and historical returns has been pretty consistent — taking additional credit risk by lending to lower quality companies produces higher returns and higher volatility.

Using the historical data set I’m looking at, you will see that much like our example of term risk, credit risk is only beneficial to a certain point.

For example, junk bond returns are higher than BBB bonds, but they come with 73% greater volatility – not exactly something you want to see in the portion of your portfolio dedicated to safety.

Now that we’ve laid the foundation for how bond returns are measured as well as the drivers of that return, I’d like to turn my attention to one of the biggest misconceptions in my career: the value of individual bonds.

One of the biggest misconceptions in my career is the value of individual bonds.

Resource: Individual Bonds vs Bond Funds: Which Should Be in Your Portfolio?

Investors who hold individual bonds tend to believe the implications of interest rate fluctuations don’t impact them because they will receive their principal value on an individual bond if it is held to maturity. Similarly, some people perceive bond funds to be riskier, since they never mature and fluctuate in price every day.

While it’s true that holding an individual bond to maturity will result in the return of principal if the bond issuer doesn’t default, those nominal dollars will be worth less with inflation and during periods of higher interest rates.

Additionally, the lack of price volatility in individual bonds is an illusion. Individual bond prices fluctuate every day, even if held to maturity, but you may not notice if the bond isn’t re-priced every day.

Finally, individual bonds mature and most bond funds do not — but most individual bonds are part of a bond portfolio that never matures, as investors usually reinvest the proceeds of maturing bonds into new bonds.

In other words, a portfolio of individual bonds is actually a form of a bond fund, but with four distinct disadvantages…

1. Individual Bonds Often Mean Higher Costs

If you think your individual bond portfolio is free, think again.

The cost of an individual bond is hidden and very difficult to measure since it is baked into the purchase price and yield. Rather than charging investors a commission to purchase a bond, a broker-dealer sells you the bond at a “mark-up,” or a higher price than they paid.

These mark-ups can be as high as 5% of the bond’s original value. A 2015 study published by Lawrence Harris, former chief economist at the Securities and Exchange Commission, estimated the average transaction costs for retail-size trades is 0.85%.

Unfortunately, the bond market isn’t a level playing field. Most investors, and even many financial advisers, don’t have the tools to know whether a bond is competitively priced at the time of purchase.

Investment fees matter regardless of asset class, but in a low-return area such as bonds, it is arguably more important. So even though you might think your individual bond portfolio is costless, it is typically far more expensive than owning a bond fund.

2. Individual Bonds Can Create Unnecessary Cash Drag in Your Portfolio

Cash drag: the opportunity cost of not being able to reinvest interest and principal on individual bonds in an efficient manner.

Let’s say you own a $100,000 corporate bond yielding 2.5% with interest payments made twice a year. Every six months, that bond will generate $1,250 in interest.

If this interest is supposed to be a part of your fixed income allocation, you won’t be able to purchase another individual bond in that small of an increment. As a result, you are likely to have the interest sit in cash earning next to nothing – hence the term “cash drag.”

A bond fund, on the other hand, holds thousands of bonds with different yields, maturities, and durations. This means that managers can reinvest bond proceeds into new bonds on a daily basis at current market rates.

This eliminates cash drag and allows bond funds to better benefit from fluctuating interest rates because they act as a daily dollar-cost-averaging mechanism.

This is particularly important in a rising interest rate environment, as bond fund managers are able to more efficiently reinvest proceeds from their bond portfolios into new bonds with higher rates of return.

3. If You Invest in Individual Anything, There’s a Lack of Diversification

Basic financial theory tells us that risk and return are related, which implies that investors should be compensated for taking additional risk.

Individual bond portfolios are frequently exposed to concentrated position risk – also known as unsystematic or idiosyncratic risk – while providing no additional compensation to investors. This risk could be easily avoided through the cheap diversification that bond funds provide.

For example, the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index (BND) holds nearly 19,000 positions with a rock bottom expense ratio of 0.04%.

Broad diversification isn’t just about the number of holdings. A properly diversified bond portfolio should use funds that contain securities with a variety of interest rates, durations, credit qualities, geographies, etc.

In my opinion, it requires at least a $10 million fixed income allocation to properly diversify a portfolio of individual bonds in a cost-efficient manner, but even then you can achieve better diversification by utilizing bond funds. Particularly when you think about this final disadvantage of individual bonds…

4. Without Bond Funds, You Might Miss Out on Global Exposure

Investors shouldn’t limit themselves to just the U.S. bond market. Global fixed income is one of the biggest investable asset classes and a tremendous source of diversification, yet this is an area where investors are routinely underexposed.

Using global bonds with hedged currency exposure has historically provided a dramatic reduction in volatility. Each country’s yield curve is shaped differently, and the factors that impact change in yields are lowly correlated across countries. Another reason for the reduction in volatility is that global bonds add to the number of issuers in a portfolio and, thus, diversifies among different credit risks.

Not only would it be challenging to sufficiently diversify across a variety of countries using individual bonds, the currency hedges required to capture the diversification benefit of this asset class are costly and complicated propositions for an individual bondholder.

Bonds play an important role in reducing your portfolio’s volatility, but historically low interest rates make the disadvantages of individual bonds versus bond funds even more prevalent.

Investors using individual bonds for their fixed income allocation would be well served to reconsider their outdated strategy.

One final closing thought that perhaps I should have kicked off the episode with…

The primary purpose of your bond allocation is to decrease the volatility of your overall portfolio – not to earn the biggest return possible.

When you start reaching for additional returns in this part of your portfolio, you start taking on substantially more risk in the part of your portfolio that is supposed to help reduce volatility.

And just like stock market movements are impossible to predict, bond market fluctuations (although nowhere near as severe as those of the stock market) are equally impossible to predict.

Rather than try to predict movements in the bond market, you should focus on the things you can control in this portion of your portfolio such as costs, our exposures to term and credit risks, and diversification.

Resources

- Individual Bonds vs Bond Funds: Which Should Be in Your Portfolio?

- Schedule a 15-minute call with my to discuss your porfolio diversification

Get Your Finance Questions Answered

Do you have a financial or investing question you want answered? Submit your question through the “Ask Me Anything” form at the bottom of my podcast page.

If you enjoy the show, you can subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts, and please leave me a review. I read every single one and appreciate you taking the time to let me know what you think.

Until next time, to long-term investing!

About the Podcast

Long term investing made simple. Most people enter the markets without understanding how to grow their wealth over the long term or clearly hit their financial goals. The Long Term Investor shows you how to proactively minimize taxes, hedge against rising inflation, and ride the waves of volatility with confidence.

Hosted by the advisor, Chief Investment Officer of Plancorp, and author of “Making Money Simple,” Peter Lazaroff shares practical advice on how to make smart investment decisions your future self with thank you for. A go-to source for top media outlets like CNBC, the Wall Street Journal, and CNN Money, Peter unpacks the clear, strategic, and calculated approach he uses to decisively manage over 5.5 billion in investments for clients at Plancorp.

Support the Show

Thank you for being a listener to The Long Term Investor Podcast. If you’d like to help spread the word and help other listeners find the show, please click here to leave a review.

Free Financial Assessment

Do you want to make smart decisions with your money? Discover your biggest opportunities in just a few questions with my Financial Wellness Assessment.