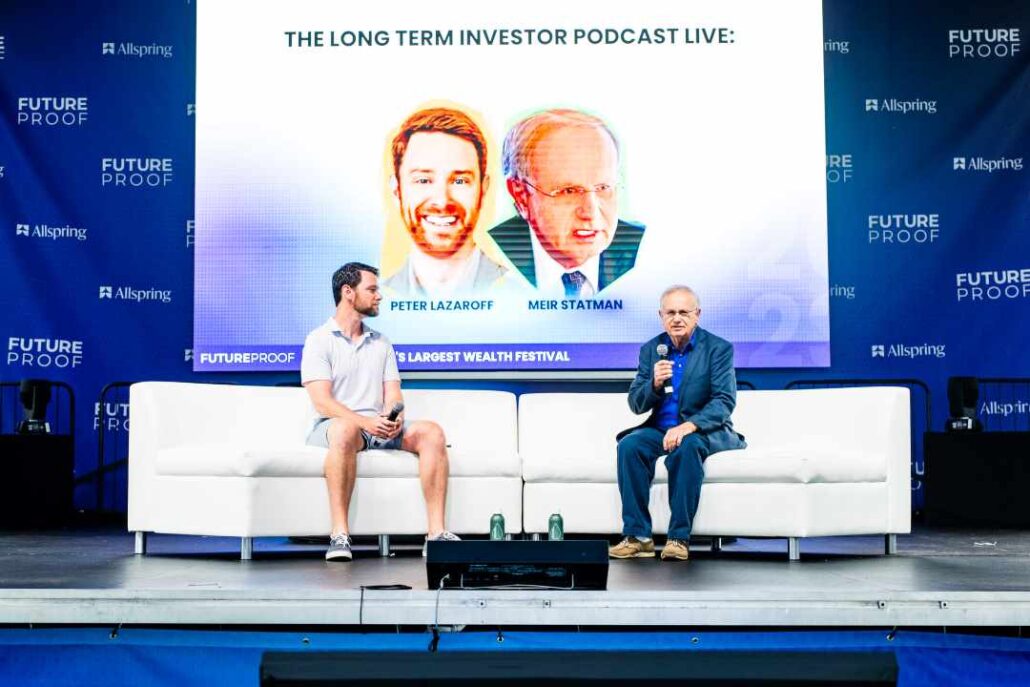

Live from Future Proof, the world’s largest wealth festival, Meir Statman talks about the evolution of behavioral finance and how the latest generation of behavioral finance focuses on holistic well-being.

Listen now and learn:

- The three generations of behavioral finance

- The difference between “errors” and “wants”

- The tradeoffs between a financially optimal and behaviorally optimal portfolio

Listen Now

Show Notes

Meir’s research focuses on understanding how investors and managers make financial decisions and how these decisions are reflected in financial markets.

The questions he addresses in his research include: What are investors’ wants and how can we help investors balance them? What are investors’ cognitive and emotional shortcuts and how can we help them overcome cognitive and emotional errors? How are wants, shortcuts, and errors reflected in choices of saving, spending, and portfolio construction? How are they reflected in asset pricing and market efficiency?

His wildly impressive full bio is listed at the end of this post. Here are my notes from this fascinating conversation…

What is Behavioral Finance? (2:00)

Behavioral finance is the study of the behavior and the decisions made by normal people, and how those decisions are reflected in financial markets. It is distinguished from standard finance, which is focused on the way purely rational people make decisions and how those decisions are reflected in financial markets. Although behavioral finance is fairly mainstream these days, it was nonexistent when Meir’s paper was published in the 1980s.

Meir appreciates how rational people are defined in a famous paper from Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani in 1961. They say that rational people prefer more wealth to less and are indifferent to the form of wealth.

Meir’s first major behavioral finance paper in 1984 takes that definition a step further by concluding that dividends do not matter to a rational investor. Why? Because if you don’t get a dividend from a company, then you can create homemade dividends by selling a few shares to get whatever “income” you want.

But as Meir points out, people do in fact care very deeply about dividends because (1) they distinguish between capital and income and (2) because they hate to dip into capital. And while this may not be rational, it is perfectly normal.

The article was published in the Journal of Financial Economics, which was a top finance journal. What I found interesting is that he and his co-author, Hersh Shefrin, didn’t expect it to get published. They were mostly looking to get feedback that would help them later. Meir compares getting a paper published in an academic journal of that caliber to a student applying to Harvard—the standards are incredibly high and very few submissions get accepted.

Meir attributes a large bit of luck to the fact that the person reviewing their work was Nobel Laureate Fischer Black, who was known to be an open-minded thinker. To publish a paper on a behavioral finance topic, before that was even what it was being called, was truly innovative.

Dick Thaler and Bob Shiller were also doing similar work at that time, and both have since gone on to win Nobel Prizes. They were all building on the work of people like Kahneman and Tversky as well as other cognitive psychologists to create what we now think of as the first generation of behavioral finance.

The first generation of behavioral finance identified people as irrational, which meant dealing with cognitive and emotional errors.

The second generation of behavioral finance acknowledges that non-wealth-enhancing, “irrational” behavior is quite normal. The key idea here is delineating an error from a want.

Meir shares a variety of choices a person might make that are errors from a purely wealth-enhancing perspective, but that carry certain utilitarian, expressive, and emotional benefits to the person making those choices.

The latest evolution of behavioral finance goes a step further with this idea and focuses more on holistic well-being, which we dive into a bit later in the conversation.

Portfolio Implications of Behavioral Finance (13:00)

Much like in Meir’s 1984 paper on investors’ preference for dividends, the wants of investors show up in other areas of a portfolio in ways that don’t always perfectly align with wealth-maximizing behavior.

Take hedge funds for example. They aren’t inherently bad, but the average hedge fund is more costly than a low-cost, diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. They also utilize active management strategies such as marketing timing and security selection that have (at best) mixed and uncertain benefits.

Meir describes a scenario where he met a person from the audience at one of his presentations. The man said: “I invest in hedge funds.” But what Meir suggests the gentleman is really trying to say is: “I am a wealthy man.”

We know that hedge fund minimums might be $500,000 or $1 million, and not everyone can afford that. The man didn’t brag about his riches because that’s socially unacceptable, but he found a way to mention that he invests in hedge funds. That’s a more socially acceptable way of signaling wealth and status, much like your car or clothes do.

When people amass significant wealth, they begin to think that a portfolio of low-cost ETFs and mutual funds isn’t good enough. They feel that their greater wealth requires something more complex. Plus, they want something more interesting to talk about with their colleagues. Thus, that want isn’t an error from a behavioral perspective because it helps meet expressive and emotional benefits.

Similarly, financial advisors know that clients sometimes want a percentage of money on the side to invest in individual stocks. Even though the data overwhelmingly suggests that this is an error, it can be a reasonable choice if it enhances their well-being without materially hurting them financially, should the capital not perform as well.

I asked Meir how he thinks an optimal portfolio from a Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) perspective differs from an optimal portfolio from a behavioral standpoint. After all, I can build a perfect portfolio from a purely wealth-enhancing perspective, but it doesn’t matter one bit if an investor can’t stick with it through thick and thin.

Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) seeks to build a well-balanced investment portfolio that maximizes returns while minimizing risk. It achieves this by selecting assets that offer the best tradeoff between expected return and risk. When you build such a portfolio, there will always be winners and losers, but the important thing is how the different investments interact with each other.

In practice, that can be challenging (and maybe even frustrating) for investors who are naturally averse to losses on an absolute or relative basis. Meir compares the optimal MPT portfolio to the optimal behavioral portfolio based on how one might be served a steak dinner.

When we visit a steakhouse, we want to have the steak on one portion of the plate with the potatoes and vegetables on the other side. That is the equivalent of a behaviorally optimal portfolio. On the other hand, a mean-variance portfolio following the principles of Modern Portfolio Theory is like putting all of those foods into a blender and drinking them with a straw.

Deviating from the blended steak dinner portfolio might not always be mathematically optimal, but it can be what’s in an investor’s best interest because it is fulfilling a “want.”

Making Behaviorally Optimal Decisions to Minimize Regret (21:00)

This applies not only to portfolio design but also to portfolio implementation. Meir describes the choice between investing a large sum of cash all at once versus dollar-cost averaging that money into the market over time.

I talk about this in more detail in Episode 117 “What’s the Best Strategy for Investing a Large Amount of Cash?”

The math is clear: Investing all at once is the financially optimal choice, but dollar-cost averaging can be easier from a behavioral perspective because it helps minimize regret.

Regret is a cognitive emotion that is strongest when you can clearly see the alternative path after making a decision. For investment decisions, the alternative path is highly quantifiable in hindsight, and that makes it easy to feel regret if you experience a bad outcome.

Financial Advisors as an Educator and Coach for Well-Being (28:30)

This was my favorite part of our conversation.

In the third generation of behavioral finance, irrationality is still normal, but the focus is more on people wanting to enhance their holistic well-being, which includes financial well-being but also much more. There are domains of well-being related to family, health, work, education, religion, society, etc.

Finding ways to convert money into well-being is really important. Financial advisors are evolving to focus more on holistic well-being without detracting too much from a client’s wealth. That’s why Meir prefers to call financial advisors “well-being advisors.”

For example, Meir shared ideas of how a financial advisor is well-positioned to help the overall well-being of people approaching or recently entering retirement

During working years, people move income into capital in the form of savings, whether it’s a 401(k) or some other means. Good savers accumulate substantial amounts of money by the time they retire. But when they retire and no longer have a regular income, dipping into that capital is a very hard transition because saving/scarcity habits built over the course of your career are hard to break.

An advisor is well positioned to aid in these situations to make sure that (1) people don’t feel guilty about spending their money and (2) that their spending aligns with their holistic well-being.

For example, when you ask people what is really important for their holistic well-being, they often say family first. And yet, people wait to share their wealth with their family until they are in their 80s or have already passed. Meir argues that the time to share wealth is during your lifetime, because “it is better to give with a warm hand than a cold one.” Adult children in their 20s, 30s, and 40s can benefit more from financial assistance than they can through inheritance in their 50s or 60s.

I asked Meir what research shows where people place the importance of money relative to other domains of well-being. Meir said that family and health are often the highest ranked. At first, I was surprised at how important work was to well-being, but it makes sense when you realize that your profession is such a large part of your identity.

But Meir emphasizes that money is still very important. He disagrees with the notion that after $75,000 in income, additional income doesn’t matter much to well-being. People gain status from having money. People gain a sense of power with money. Having money reduces people’s fears. For things people tend to value most, like family or health, you can’t necessarily have those things without money. So you need money for everything, but money is not everything.

Another quote of Meir I really like is “Money is a weigh station for well-being.” And again, finding ways to convert dollars into well-being is the role a financial advisor can play.

Meir Statman’s Full Bio

Meir Statman is the Glenn Klimek Professor of Finance at Santa Clara University. His research focuses on behavioral finance. He attempts to understand how investors and managers make financial decisions and how these decisions are reflected in financial markets. His most recent book is “Behavioral Finance: The Second Generation,” published by the CFA Institute Research Foundation.

The questions he addresses in his research include: What are investors’ wants and how can we help investors balance them? What are investors’ cognitive and emotional shortcuts and how can we help them overcome cognitive and emotional errors? How are wants, shortcuts, and errors reflected in choices of saving, spending, and portfolio construction? How are they reflected in asset pricing and market efficiency?

Meir’s research has been published in the Journal of Finance, the Journal of Financial Economics, the Review of Financial Studies, the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, the Financial Analysts Journal, the Journal of Portfolio Management, and many other journals. His research has been supported by the National Science Foundation, the CFA Institute Research Foundation, and the Investment Management Consultants Association (IMCA).

Meir is a member of the Advisory Board of the Journal of Portfolio Management, the Journal of Wealth Management, the Journal of Retirement, the Journal of Investment Consulting, and the Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, an Associate Editor at the Journal of Behavioral Finance and the Journal of Investment Management, and a recipient of a Batterymarch Fellowship, a William F. Sharpe Best Paper Award, two Bernstein Fabozzi/Jacobs Levy awards, a Davis Ethics Award, a Moskowitz Prize for best paper on socially responsible investing, a Matthew R. McArthur Industry Pioneer Award, three Baker IMCA Journal Awards, and three Graham and Dodd Awards. Meir was named as one of the 25 most influential people by Investment Advisor. He consults with many investment companies and presents his work to academics and professionals in many forums in the U.S. and abroad.

Meir received his Ph.D. from Columbia University and his B.A. and M.B.A. from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Resources:

- Meir Statman’s full bio

- Dividend Policy, Growth, and the Valuation of Shares by Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani

- Explaining investor preference for cash dividends by Hersh M. Shefrin and Meir Statman

- EP. 117: What’s the Best Strategy for Investing a Large Amount of Cash?

Submit Your Question For the Podcast

Do you have a financial or investing question you want answered? Submit your question through the “Ask Me Anything” form at the bottom of my podcast page.

If you enjoy the show, you can subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts, and please leave me a review. I read every single one and appreciate you taking the time to let me know what you think.

About the Podcast

Long-term investing made simple. Most people enter the markets without understanding how to grow their wealth over the long term or clearly hit their financial goals. The Long Term Investor shows you how to proactively minimize taxes, hedge against rising inflation, and ride the waves of volatility with confidence.

Hosted by the advisor, Chief Investment Officer of Plancorp, and author of “Making Money Simple,” Peter Lazaroff shares practical advice on how to make smart investment decisions your future self with thank you for. A go-to source for top media outlets like CNBC, the Wall Street Journal, and CNN Money, Peter unpacks the clear, strategic, and calculated approach he uses to decisively manage over 5.5 billion in investments for clients at Plancorp.

Support the Show

Thank you for being a listener to The Long Term Investor Podcast. If you’d like to help spread the word and help other listeners find the show, please click here to leave a review.

Free Financial Assessment

Do you want to make smart decisions with your money? Discover your biggest opportunities in just a few questions with my Financial Wellness Assessment.