Concentrated stock positions typically emerge through employee compensation, inheritance, or a singularly successful investment. But in all cases, a large individual stock position introduces unnecessary risk to your portfolio.

Listen now and learn:

- Why investors tend to avoid diversifying concentrated stock positions

- Four ways to diversify concentrated stock positions

- How SMAs supercharge tax loss harvesting efforts to offset capital gains

- When more advanced strategies such as exchange funds or option collars are best

Listen Now

Show Notes

Concentrated stock positions typically emerge through employee compensation, inheritance, or a singularly successful investment. But in all cases, a large individual stock position introduces unnecessary risk to your portfolio.

In this episode, we’ll dissect the complexities of these positions, explore the inherent risks, and provide guidance on strategically managing and, if necessary, diversifying these holdings.

Why Investors Own Concentrated Stock Positions

There are three scenarios we encounter most frequently at Plancorp.

The first are individuals who acquire a concentrated stock position through employee compensation plans, whether that’s stock options, restricted stock units, or other equity-based compensation as part of their benefits package.

Over time, as these options vest or, as the company grows and succeeds, employees may find that a substantial portion of their wealth is tied up in that company’s stock.

Another frequent source of concentrated stock positions is inheritance. It’s common for relatives to avoid selling their most highly appreciated positions with the idea that, at death, the cost basis will step up for their heirs, which allows them to sell the position at no gain. There are other instances where the deceased’s trust is such that there is no step up in basis, but either way…inheritors of wealth often find themselves holding a significant amount of a single stock.

The third scenario that comes up, particularly with new and prospective clients, is an individual holding an individual stock that has performed exceptionally well and now makes up a significant portion of their wealth.

Challenges Posed by Concentrated Stock Positions

While a concentrated stock position can be the result of good fortune, loyalty, or legacy, it presents its holder with unique challenges.

- Risk Exposure

The most obvious and often cited challenge is the risk of lack of diversification. As the old adage goes, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.” A portfolio dominated by one stock is highly vulnerable to that company’s fortunes. A significant downturn in that company or sector can result in a large financial loss.

- Emotional Attachment

Having a large portion of wealth tied up in a single stock can create a strong emotional connection to that company. This emotional bias can cloud judgment and make it difficult to make objective decisions about when to sell or how to manage the position.

- Reduced Liquidity

A concentrated position might not always be easily sellable, especially if it’s a significant portion of the company’s total shares or if the stock’s trading volume is low. Liquidating a large position can also move the market, potentially resulting in a lower selling price.

- Tax Implications

Selling a large stock position, especially one that has appreciated significantly, can have substantial capital gains tax implications. This consideration can deter investors from diversifying their position, even when it might be in their best interest—so tax implications create both a financial and behavioral challenge for investors to overcome.

- Opportunity Cost

To me, the most overlooked challenge posed by concentrated stock positions is the opportunity cost. By remaining heavily invested in one stock, investors potentially miss out on gains from other companies or sectors. I dedicate an entire episode to this topic, but here’s a short overview:

Only about 4% of stocks make up the total US stock market return. And two-thirds of all stocks underperform the total US stock market. Two-thirds!

I think that people sometimes see large gains on their concentrated position over a certain period of time, but don’t realize they probably are underperforming the broad stock market. And in instances where they are outperforming the broad stock market, let me share one more statistic: roughly 40% of all stocks (all stocks!) have suffered a permanent 70%+ decline from their peak value.

So not only do concentrated stock positions create meaningful opportunity costs, but (as I mentioned earlier) they are incredibly risky in the first place.

Strategies for Unraveling Concentrated Stock Positions

Strategically managing concentrated stock positions starts with setting clear objectives. If you’re relying on this stock for retirement, your strategy might differ from someone who views it as a bonus or a position that will be passed on to future generations.

With that in mind, here are four ways to manage concentrated stock positions:

Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs) with Tax Loss Harvesting Emphasis

If you’re worried about the tax implications of selling off parts of your concentrated stock, tax loss harvesting to offset the capital gains can be an effective way to move towards a more diversified portfolio without incurring a big tax bill.

Tax loss harvesting is an investment strategy where underperforming investments are sold to realize losses, which can offset taxable capital gains from other investments. Later, the sold investments can be replaced with similar ones to maintain the desired portfolio allocation.

The problem with relying on mutual funds or ETFs for tax loss harvesting opportunities is that they are typically only at a loss when the market is in a correction or bear market.

Enter Separately Managed Accounts (SMAs), which are like having your very own private mutual fund or ETF. But unlike owning a mutual fund or ETF, you can tax loss harvest even when the market is up and the overall position isn’t at a loss. Let me explain.

SMAs enable investors to take advantage of tax-loss harvesting opportunities by selling losing positions within what I’m referring to as your own private mutual fund and buying similar stocks to maintain their exposure to the market. For example, maybe your SMA manager sells Coca-Cola at a loss and buys Pepsi…or sells Johnson & Johnson at a loss and buys Pfizer in its place…or sells ExxonMobil and buys Chevron…you get the point.

Unlike an ETF or mutual fund, which requires the entire index to be at a loss in order to perform tax loss harvesting, investors can harvest losses at the individual security level within an SMA, which can then be used to sell portions of the concentrated stock position that is trading at a gain.

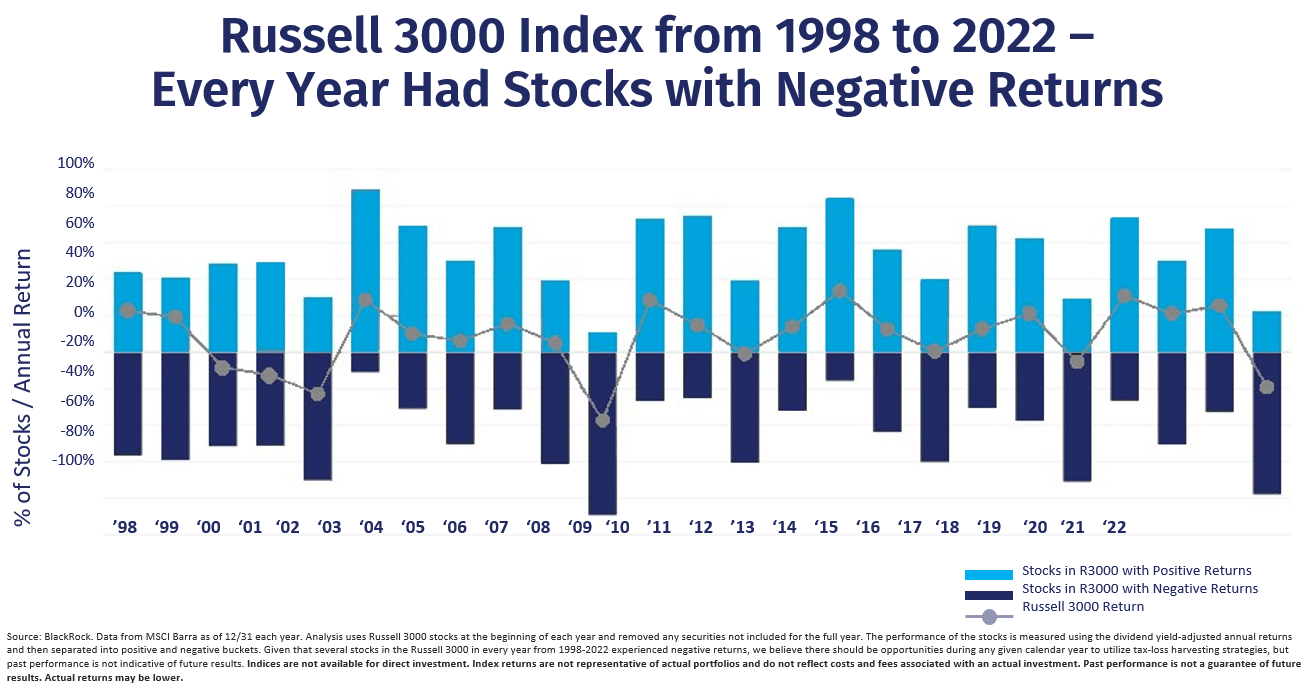

You’d be surprised how many stocks are trading at a loss in years when the overall market is up, which you can clearly see in the chart below.

I go into more detail on this in Episode 95: What Is Direct Indexing?

Contribute Concentrated Stock to an Exchange Fund

Exchange funds are a specialized investment tool designed primarily for investors holding large, concentrated stock positions. These funds offer a mechanism to diversify such positions without triggering immediate capital gains taxes.

Think of an exchange fund as a potluck but for stocks. Various investors can contribute their concentrated stock positions into a pooled fund that seeks to track a broad market index such as the Russell 3000.

Investors contribute their appreciated shares of a single stock to the exchange fund. In return, they receive a pro-rata share of the fund, which comprises a diversified portfolio of various stocks contributed by all participants. In essence, they’re “swapping” their single-stock position for a share in a broader portfolio.

The tradeoff for this immediate diversification without capital gains is a multi-year loss of liquidity as these funds typically have lock-up periods that prevent you from accessing the capital without penalty, although it’s worth noting that death is a common exception in which you can get instant liquidity with no early withdrawal penalties.

But to me, the lack of liquidity is a small concession to make in exchange for instant diversification without any immediate tax bill. Instead of having a substantial portion of one’s wealth tied to a single stock, investors get exposure to a range of assets, reducing the impact of any single stock’s poor performance.

Instead of selling a large stock position and incurring capital gains tax, swap funds allow investors to defer this tax. The tax liability is postponed until they eventually sell their shares in the exchange fund if they ever choose to do so.

Create Greater Certainty With Option Collars

An options collar is akin to putting bumpers on a bowling lane. Just as these bumpers prevent your ball from going into the gutter, ensuring it stays within certain bounds, an option collar sets a ceiling and a floor for your stock’s price, limiting both potential loss and gain.

In essence, an option collar involves holding the stock, buying a put option (which gives you the right to sell the stock at a predetermined price, the ‘strike price’), and selling (or “writing”) a call option (where you agree to sell the stock if it reaches a certain higher price). The combination of these actions forms a ‘collar’ around the stock’s potential price movement.

Let’s say you own a stock currently priced at $100. You might buy a put option with a strike price of $90 and sell a call option with a strike price of $110. This means if the stock price falls, you can still sell it for $90 (limiting your loss). But if the stock price rises above $110, the call option buyer can buy it from you at that price (limiting your gain).

The primary advantage is that it provides a safety net against a drop in the stock’s price. By purchasing a put option, you know the minimum amount you can sell the stock for, thus capping potential losses.

The most significant drawback is that your gains are limited. If the stock price surges, you won’t benefit beyond the call option’s strike price since the call option buyer will likely exercise their right to buy the stock from you at that predetermined price. Similarly, by locking in a range of outcomes for a single stock rather than diversifying into broad market exposure, you are giving up the upside that comes with owning the entire market.

Tax implications are another potential downside, especially if the options are bought and sold without being exercised. It’s crucial to keep detailed records and possibly consult with a tax professional to ensure compliance and optimization. And if the call option is exercised, you’ll be incurring capital gains at a time that might not be optimal.

Option collars can be very effective, but it really depends on how and when they’re used.

Diversify Gradually

It’s not always about complex financial instruments. Sometimes, the best strategy can be to diversify away slowly and systematically from your concentrated position. This can be done by setting up regular intervals where you sell a portion of your stock and reinvest in other areas.

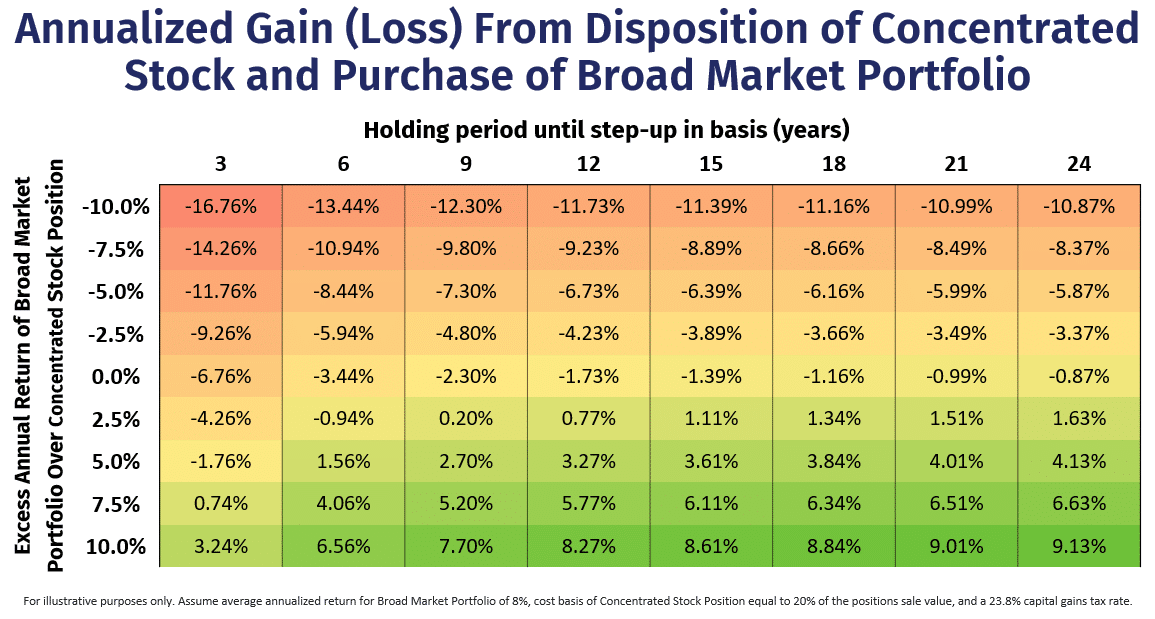

After all, it usually doesn’t make sense to let the tax tail wag the dog. And if you truly believe in the historical research showing that individual stocks dramatically underperform the overall market, then the outcome of selling a stock, paying the capital gains, and reinvesting in the broad market will be determined by: (1) how the stock performs relative to the broad market after the sale and (2) how long the owner would have held the stock otherwise (until a step-up in cost basis at death):

In only a small number of cases would the impact of taxation negate the benefits of selling, so most concentrated stock owners should probably reduce the weight they put in their tax bill when discussing a strategic plan to reduce exposure to a concentrated position.

Resources:

Submit Your Question For the Podcast

Do you have a financial or investing question you want answered? Submit your question through the “Ask Me Anything” form at the bottom of my podcast page.

If you enjoy the show, you can subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts, and please leave me a review. I read every single one and appreciate you taking the time to let me know what you think.

About the Podcast

Long-term investing made simple. Most people enter the markets without understanding how to grow their wealth over the long term or clearly hit their financial goals. The Long Term Investor shows you how to proactively minimize taxes, hedge against rising inflation, and ride the waves of volatility with confidence.

Hosted by the advisor, Chief Investment Officer of Plancorp, and author of “Making Money Simple,” Peter Lazaroff shares practical advice on how to make smart investment decisions your future self with thank you for. A go-to source for top media outlets like CNBC, the Wall Street Journal, and CNN Money, Peter unpacks the clear, strategic, and calculated approach he uses to decisively manage over 5.5 billion in investments for clients at Plancorp.

Support the Show

Thank you for being a listener to The Long Term Investor Podcast. If you’d like to help spread the word and help other listeners find the show, please click here to leave a review.

Free Financial Assessment

Do you want to make smart decisions with your money? Discover your biggest opportunities in just a few questions with my Financial Wellness Assessment.