If there was a perfect way to invest, it might be summed up in a single phrase: buy low and sell high. While it might seem impossible to do this in practice, rebalancing your portfolio helps achieve this ideal.

It’s worth taking the time to ensure you fully understand what rebalancing is and how to do it properly—as well as knowing the challenges that can get in the way of making it happen and how to avoid them.

It’s Critical You Learn to Rebalance Your Portfolio

Imagine you’ve just created a new portfolio with a specific mix of stocks and bonds based on a personalized financial plan. The portfolio looks as you designed it on day one, but your investments drift from their original allocations as the market naturally shifts around.

If stocks outperform bonds, you end up with more stocks (and, thus, more risk) than you originally intended. Consequently, you’re no longer invested according to plan, even if you’ve done nothing at all.

How do you solve this problem? You rebalance.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean that the allocations you started with inherently represent the perfect portfolio that must remain precisely on point over time. But we’re assuming that you set your initial strategy as a long-term investor based on your specific needs, circumstances, and goals.

As your portfolio inevitably drifts from the set target over time, you need to manage that movement and periodically bring things back into alignment with your strategy and intentions for your investments.

When you rebalance your portfolio, you sell asset classes that have done well and buy others that have done poorly—in other words, you buy low and sell high. Another strategy is using any new money you contribute to your portfolio to buy more of whatever is underweight at the time. In both instances, your trades are not a matter of random guesswork or emotional reactions.

Disciplined rebalancing offers a rational approach to securing some of your past gains, managing your future risk exposure, and remaining invested as planned so you can capture future expected gains over the long-run.

A Simple Example of Rebalancing

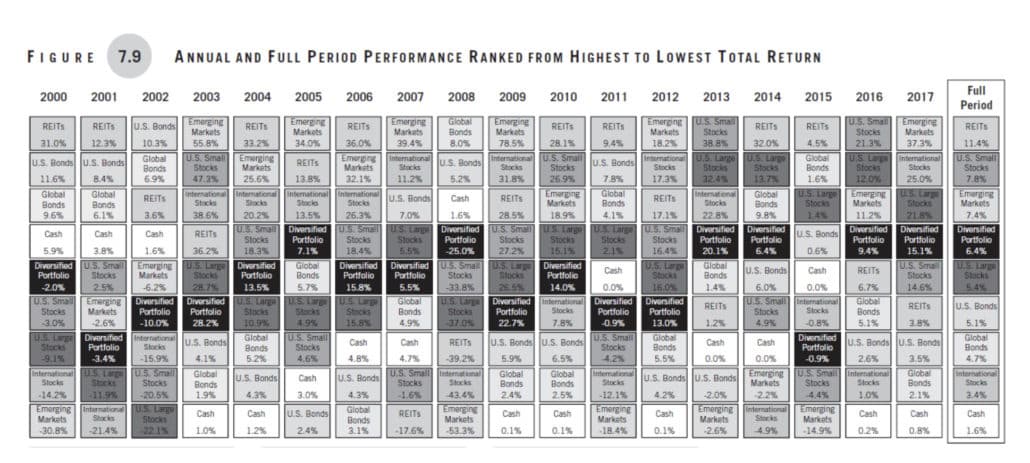

Let’s look at how this works with a simple example using historical data. Below is a table from my book that shows annual returns for various asset classes.

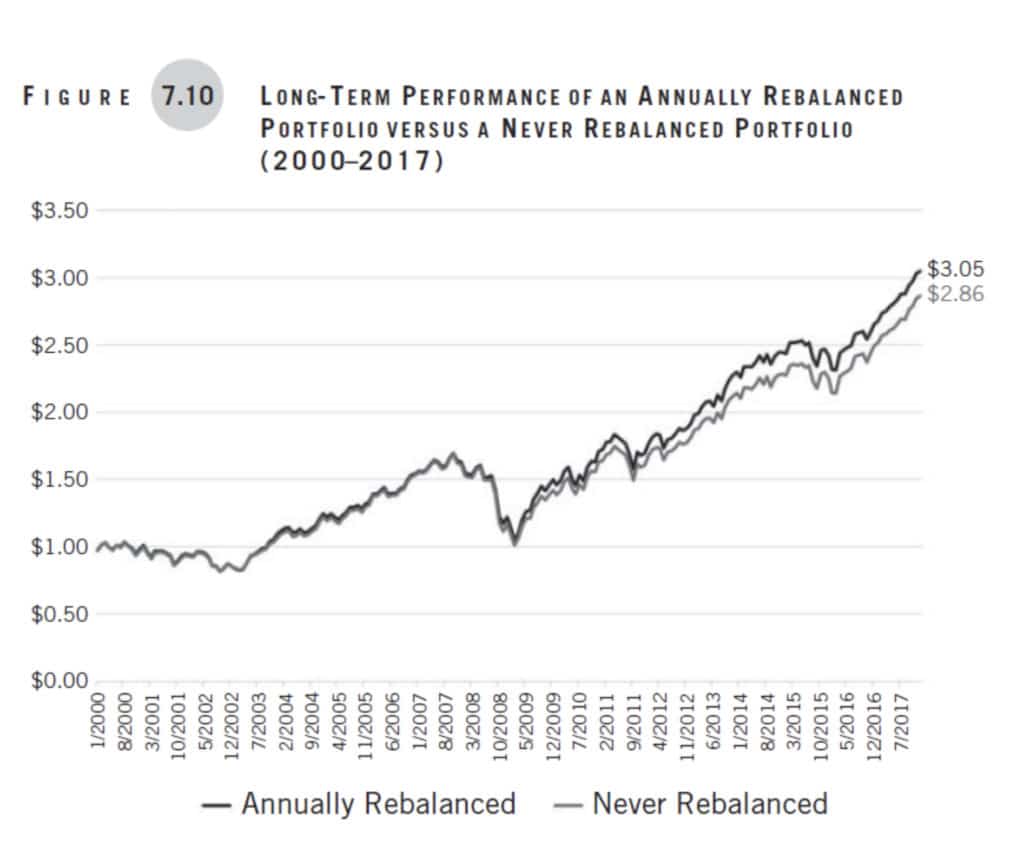

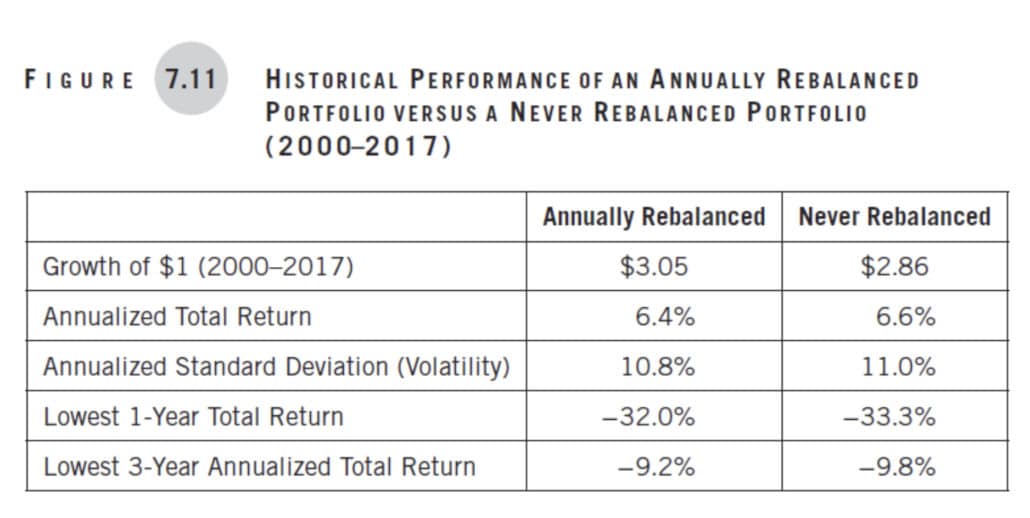

The annually rebalanced portfolio ends up with more money because it exhibits less volatility—and compound interest works better with lower volatility. As an added bonus, losses during the worst-performing periods for the annually rebalanced portfolio weren’t quite as bad as the portfolio that was never rebalanced.

Of course, rebalancing in real life is often more complicated than this straightforward example. While we can talk about theoretical portfolios using simple index funds in a single account, my experience tells me most investors don’t use such an approach.

To be clear, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with a pure index strategy; it’s actually one of the three evidence-based investing strategies we implement for our clients at Plancorp. But again, in practice, most people don’t use (or at least, don’t stick with) this simple index strategy.

It’s more common to see people with multiple subcategories within various asset classes, which introduces more positions into their portfolio. People also usually have more than one account and their holdings are rarely divided in such a way that the same positions are in each of the different accounts in the same percentages.

These realities mean that simplified examples of rebalancing can make the process easier said than done. And that’s before we even get into the other major factor that appears in the real world that theories on paper just don’t account for, but that derails many investors: human behavior.

The Emotional Challenge of Rebalancing

On paper, the process to rebalance your portfolio is simple and easy. Everyone understands the logic of buying low and selling high. But when it’s time to actually take action, emotions tend to get in the way for most investors.

Down markets, in particular, can represent good times for rebalancing, but it might feel uncomfortable to sell some of your assets that have been doing okay in order to buy more unpopular or worse-performing ones.

I remember coaching clients through the Great Recession of 2007–2009. The S&P 500 fell roughly 60% over the course of a year and a half. If you rebalanced on a quarterly basis during that recession, you might have bought stocks when they were down 10% and then again when they were down 20%, then 30%, then 40%.

Many people struggled with the idea of selling bonds that were doing relatively well to buy stocks when the economic outlook was dire and showed little signs of improvement. At the time, the subsequent recovery was anything but obvious, and a global financial meltdown did not exactly encourage confidence in investors.

Buying into a market doing that badly is something many people think they will have no problem doing if you ask them before such an event occurs. They understand, on a logical level, that doing so is part of perfectly executing a set rebalancing strategy.

But it’s extremely difficult in the moment to set aside emotion and confidently carry on with your investment strategy when it feels bad, stupid, or scary to do so.

We saw the same thing happen in the spring of 2020 when a global pandemic began. The S&P 500 fell over 30% in about a month. Not only were people wrestling with a fast-paced bear market, but the health scare from COVID-19 made the situation seem very different than past bear markets.

When, in the moment, it genuinely feels “different this time,” following your set strategy is not easy.

If you needed to rebalance in March, you had to do so in the face of massive uncertainty. But those that were disciplined and rebalanced were handsomely rewarded with a massive rally over the summer and even into 2021.

Those who rebalance at times when it may feel the hardest to do so are often the best-positioned to capture available returns during subsequent recoveries. But it takes a huge leap of faith in the academic evidence indicating that capital markets will likely prevail over time.

My real-life examples focus on down markets because that’s when I see a greater number of people tempted to deviate from their plan, but rebalancing can also be a challenge when markets are up.

In recent years, this has often meant buying International stocks and Emerging Market stocks at a time when the S&P 500 was crushing everything. Investors that haven’t wanted to rebalance in this manner create narratives that, to them, make it obvious that buying the relative laggard is a bad idea, especially if it means selling the relative winner.

Comparing Different Rebalancing Strategies

So how can we rebalance well in the real world without letting emotions get in the way? Most rebalancing strategies fall into one of two categories:

- Time-based rules rebalance the portfolio on a predetermined interval (daily, monthly, quarterly, annually, etc).

- Threshold rebalancing means predetermining the percentage drift from a target allocation that would trigger rebalancing.

Which is the better option? I’ve done this research project twice in my career now. Unfortunately, I’ve ended up discouraged with my results in both cases because the answer has consistently been: It depends on the time period being measured.

More frequent rebalancing keeps a portfolio more closely aligned with its allocation targets, but premature selling of winning positions to buy laggards can hinder performance more than less frequent rebalancing would. This approach also triggers more taxes, which eat into net returns.

Capital gains are realized whenever a security is sold for a profit, which is likely to happen with rebalancing since you are systematically trimming positions that have grown within your portfolio.

Of course, taxes are just one of the costs to rebalancing. The other costs come in the form of time and trading fees.

If you have an advisor, the time consideration isn’t an issue because you’re paying your advisor to take systematic rebalancing off your plate. But explicit and implicit transaction costs incurred by trading mutual funds and ETFs (no, your free ETF trades aren’t actually free) can add up quickly if you rebalance too frequently.

Whether the rebalancing rules you choose to follow outperform or not will be a matter of random time period luck. Said another way: When it comes to rebalancing strategies, the best strategies can only be known with the benefit of hindsight.

But here’s what we do know about how to rebalance your portfolio the right way:

- A rebalanced portfolio generally exhibits a tighter return distribution and typically has more return per unit of risk (risk-adjusted return)

- Non-rebalanced portfolios generally are more volatile

- Emotionally, rebalancing can help with discipline and emotional control in volatile markets, which means it’s easier to stay on track (and the most important thing for the long-term investor is to stay the course).

And finally, we know that any rebalancing strategy is better than no rebalancing strategy at all.

YCharts recently issued a white paper examining how six different rebalancing strategies affected portfolio performance and risk over 25 years of history. Their conclusion points out that the differences in rebalancing strategies are not all that important as long as the rebalancing rule is consistently adhered to.

Rebalance Your Portfolio The Right Way

The most important thing you need to understand to properly rebalance your portfolio (and to keep doing it over time) is to identify what works for you. I’ll leave you with a quote from Vanguard’s research paper on rebalancing, which put it well:

“Ultimately, we believe that investors will benefit from systematic rebalancing, but we don’t find a specific rebalancing threshold or frequency that consistently outperforms other forms of rebalancing. It may behoove investors not to stress about the specifics but rather to choose a rebalancing strategy they can comfortably stick with.”

…

RESOURCE: Do you want to make smart decisions with your money? Discover your biggest opportunities in just a few questions with my Financial Wellness Assessment.

Hiya – interesting post – especially the comparison in the chart/table.

Am a bit puzzled by the Annualized Tot Returns in Fig 7.11. I think the “never rebalanced” figure may be a typo, as 2.86^(1/18) = 6.0%. which is lower than the 6.4% figure for annual rebalancing, thus supporting the case for annual rebalancing.

I guess some would say the difference in both the ann returns and vol are pretty modest. Obviously, “every little helps” but is it possible that they’re just in the error range of returns and vol one would get from a comparison of the returns and vol calculated each year ?

Anyhow, thanks again for an interesting post !

Robert (England)

Hi Robert. Thanks for the note. The way people calculate an average annualized total return is using the geometric average of monthly returns. Using the geometric average is probably what explains most of the difference, although I imagine the monthly versus annual data points also contributes some meaningful amount of difference in compounding.