If there is a universal investment ideal, it’s that every investor wants to buy low and sell high. Rebalancing does just that.

In today’s episode, I’m going to explain rebalancing at a high level with some simple examples, point out some practical to challenges rebalancing, and then talk about the best way to rebalance your portfolio.

Listen now and learn:

- The basics of rebalancing

- Practical challenges, costs, and considerations

- The pro’s and con’s of different different rebalancing strategies

As an added bonus, Peter shares how to get free access to exclusive research on the topic.

Episode

Outline

If there is a universal investment ideal, it’s that every investor wants to buy low and sell high. Rebalancing does just that.

In today’s episode, I’m going to explain rebalancing at a high level with some simple examples, point out some practical challenges for rebalancing, and then talk about the best way to rebalance your portfolio.

So let’s dive in.

Imagine you’ve just created a new portfolio with a specific mix of stocks and bonds based on a personalized financial plan. The portfolio looks as you designed it on day one, but then naturally markets shift around and your investments drift from their original allocations.

Consequently, you’re no longer invested according to plan, even if you’ve done nothing at all.

If stocks outperform bonds, you end up with too many stocks relative to bonds and thus you’re taking on more risk than you originally intended. It’s not like the starting allocations are some perfect portfolio that has to remain precisely on point, but as your portfolio drifts further from its intended target, your portfolio will need some attention.

Rebalancing takes advantage of this trend by selling asset classes that have done well and buying those that have done poorly—in other words, rebalancing ensures you buy low and sell high.

In the current example of stocks outperforming bonds, to rebalance your portfolio, you can sell some of the now-overweight stocks, and use the proceeds to buy bonds that have become underrepresented, until you’re back at or near your desired mix.

If you’re regularly adding to your portfolio on a monthly, quarterly, annual, or even ad hoc basis, another strategy is to use any new money you are adding to your portfolio to buy more of whatever is underweight at the time.

Either way, think about what is happening. Not only are you keeping your portfolio’s risk and return levels aligned with your goals, but you’re buying low (underweight holdings) and selling high (overweight holdings). Better yet, the trades are not a matter of random guesswork or emotional reactions. The feat is accomplished according to your carefully crafted, customized plan.

A Simple Example of Rebalancing

Let’s look at how this works with a simple example using historical data. There is a table in my book that that shows annual returns for various asset classes that I’ll be sure to add to the show notes.

It’s what many financial advisors refer to as the periodic table of returns, mostly because it’s a lot of returns shown in little squares, although Phil Huber created something for his blog Bps and Pieces that is more periodic table like, but that’s besides the point (although I will also link to that in the show notes).

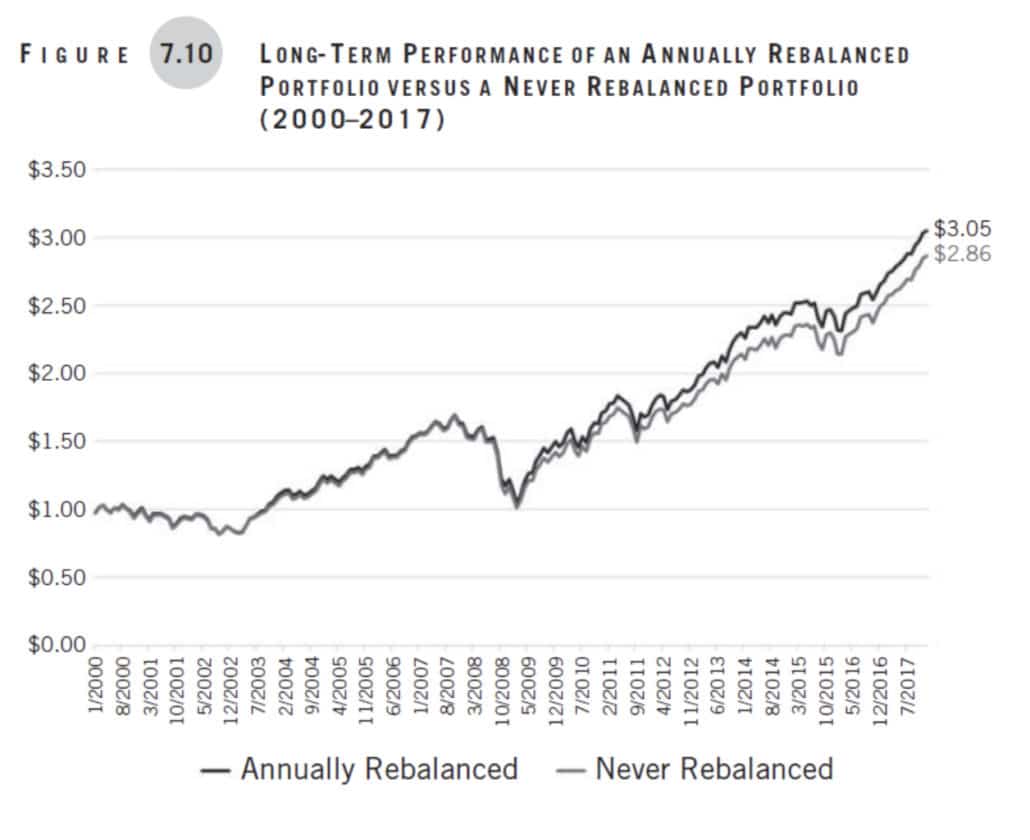

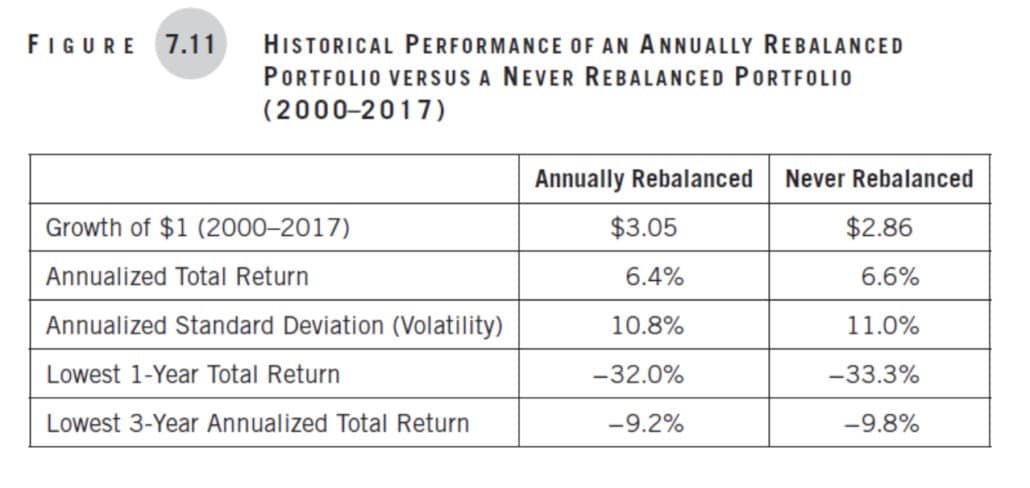

Anyways, as you will see periods of higher returns for any given asset class are often followed by periods of lower returns. In the book, I compare the outcomes of an annually rebalanced portfolio versus a portfolio that is never rebalanced.

The benefit of systematically selling asset classes that have done well and buying those that have done poorly results in the annually rebalanced portfolio ending up with more money.

That’s largely because it exhibits less volatility.

And even though it has slightly less return, the lower volatility allows the ever so slightly lower return to compound better.

This is a topic I’ve touched on before – compound interest works better with lower volatility.

As an added emotional bonus, losses during the worst-performing periods for the annually rebalanced portfolio weren’t quite as bad as the portfolio that was never rebalanced.

There’s no guarantee that rebalancing will enhance performance, but the biggest benefit of rebalancing is keeping your risk exposure in line with your risk tolerance.

If you set out to invest in a portfolio with 70 percent stocks because it meets your needs, then you don’t want to let that portfolio drift to 80 percent stocks as the result of a rising market and become riskier than you are willing or able to tolerate.

Rebalancing Isn’t Always Simple

Now, this example is pretty plain and simple, but rebalancing is often more complicated because real-life portfolios are rarely this simple.

For starters, my example uses a relatively simple index portfolio with a single account, but (in my experience) most investors don’t use such an approach.

To be clear, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with a pure index strategy, in fact it’s one of the three evidence-based investing strategies we use with Plancorp clients. There is no single portfolio that is right for everyone and an all index approach IMO is easily among the optimal options for most people.

But, even with all that said, most people don’t use an index strategy. Maybe that’s because people often want to pursue strategies that have the opportunity to beat the market or because they think an all index portfolio is too simple…I don’t know, but it’s just not super common.

More often you see people with multiple subcategories within the various asset classes, which introduces more positions.

People also usually have more than one account and their holdings usually aren’t divided such that the same positions are in each of the different accounts in the same percentages. And even if that were possible, it is probably not an ideal asset location strategy for generating the highest after-tax returns.

The tendency for investors to have more positions across more accounts than my example means there are more tradeoffs in the real-life implementation of rebalancing, but before those diving into those implementation tradeoffs, we can’t ignore the behavioral side of things.

The Emotional Challenge of Rebalancing

Like many things with investing, implementing in real time is much harder than talking about theoretically.

It’s scary to do in real time. Everyone understands the logic of buying low and selling high. But when it’s time to rebalance, your emotions make it easier said than done.

Down markets in particular can represent good times for rebalancing, but it might feel uncomfortable to sell some of your assets that have been doing okay and buy the unpopular ones.

I remember coaching clients through the Great Recession of 2007–2009 when the S&P 500 fell roughly 60% over the course of 17 or 18 months. At some point or another, most people had a hard time with the idea of selling bonds that were doing relatively well to buy stocks since the outlook for the economy was so dire and offered very little signs of improvement.

And think about: If you rebalanced on a quarterly basis during that recession, you might have bought stocks when they were down 10% and then again when they were down 20%, then 30%, then 40%, etc….in my opinion, that’s part of why you hire an advisor, to do the tough things without emotion.

Same goes for the spring of 2020 when the pandemic began and the S&P 500 fell over 30% in about a month. Not only were people wrestling with a fast-paced bear market, but the health scare made the situation seem different than past bear markets.

There was so much we didn’t know when rebalancing in march, but those that were disciplined and rebalanced were handsomely rewarded with a rip roaring rally.

In both instances – the Financial Crisis and the pandemic – those who did rebalance were best positioned to capture available returns during the subsequent recovery. But at the time, it represented a huge leap of faith in the academic evidence indicating that our capital markets would probably prevail.

On the other side of the coin, rebalancing can be a challenge when markets are up, requiring you to sell some of your best performers and rebalance into the relative laggards. In recent years, this has often meant buying International stocks and Emerging Market stocks at a time when the S&P 500 was crushing everything.

In the moment, this can feel counterintuitive, but disciplined rebalancing offers a rational approach to securing some of your past gains, managing your future risk exposure, and remaining invested as planned, for capturing future expected gains over the long-run.

Besides combatting your emotions, I mentioned there are some tradeoffs that must be considered.

If trading were free, you could rebalance your portfolio daily with precision. In reality, trading incurs fees and potential tax liabilities.

To achieve a reasonable middle ground, it’s best to have guidelines for when and how to cost-effectively rebalance.

Comparing Different Rebalancing Strategies

Most rebalancing strategies fall into one of two categories:

- Time-based rules rebalance the portfolio on a predetermined interval (daily, monthly, quarterly, annually, etc).

- Threshold rebalancing means predetermining the percentage drift from a target allocation that would trigger rebalancing.

Which is better?

I’ve done this research project twice in my career now, both times feeling discouraged with my results that were: It depends on the time period being measured.

On one hand, more frequent rebalancing keeps a portfolio more closely aligned with its allocation targets, but the potential downside is that premature selling of winning positions to buy laggards can hinder performance more than less frequent rebalancing would.

More frequent rebalancing also triggers more taxes. Think about it….capital gains are realized whenever a security is sold for a profit — which is likely to happen with rebalancing since you are systematically trimming positions that have grown within your portfolio.

Taxes are just one of the costs to rebalancing. The other costs come in the form of time and trading fees. If you have an advisor, the time consideration is not an issue because you are paying your advisor to take systematic rebalancing off your plate.

But explicit and implicit transaction costs incurred by trading mutual funds and ETFs (no, your free ETF trades aren’t actually free) can add up quickly if you rebalance too frequently.

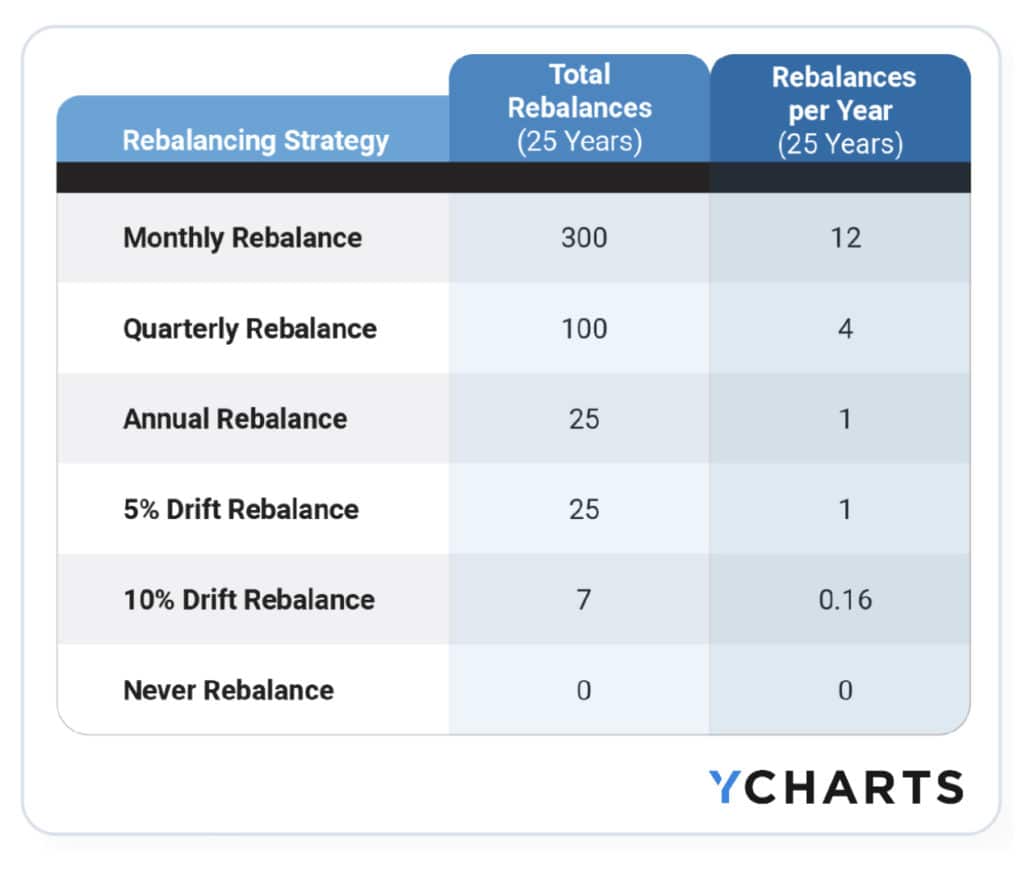

YCharts recently issued a white paper examining how six different rebalancing strategies affected portfolio performance and risk over 25 years of history, including four bull markets and three bear markets. I’ve included a special link in the show notes that lets you access the paper for free, so go check it out.

The portfolio has 6 positions that make up a globally diversified 60/40 index portfolio.

The six strategies evaluated were:

- Monthly Rebalance

- Quarterly Rebalance

- Annual Rebalance

- 5% Drift

- 10% Drift

- Never Rebalance

For the 25 years YCharts studied, here is the frequency of trading those different strategies required:

One might be surprised to learn that the differences in rebalancing strategy is not all that important as long as the rebalancing rule is consistently adhered to.

One concept the YCharts paper explores is changing the rebalancing strategy based on the type of market you are in. I firmly disagree with this premise because it requires you to know that (1) you are entering a bear market or bull market, which is extremely difficult to discern in the moment. All rebalancing studies are with the benefit of hindsight, so yes – obviously it would be best to rebalance less frequently in a bull market and less frequently in a bear market.

Secondly, the frequency or threshold you choose for rebalancing are secondary to establishing a systematic rebalancing strategy.

A set policy will trigger rebalancing events in a consistent manner, ideally balancing the needs for keeping your allocation in check and limiting the higher taxes associated with more frequent rebalancing and turnover. Whether the rebalancing rules you set outperform will be a matter of complete and random time period luck.

When it comes to rebalancing strategies, the best strategies can only be known with the benefit of hindsight.

But here’s what we definitively know:

- A rebalanced portfolio generally exhibits a tighter return distribution

- Non-rebalanced portfolios generally are more volatile

- A rebalanced portfolio typically has more return per unit of risk (risk-adjusted return)

- Emotionally, rebalancing can help with discipline and emotional control in volatile markets, which means it’s easier to stay on track….and the most important thing for the long-term investor is to stay the course

- Any rebalancing strategy is better than no rebalancing strategy at all

Vanguard has a rebalancing study – Vanguard has a study on everything, which I suppose is what you should expect when you manage $5 trillion. Yeah, they’re low cost, but low costs on $5 trillion still amounts to a lot of money to spend on research to better investor experiences…

Anyways, I like the quote from Vanguard’s paper, which is a bit more technical and practioner focused than the YCharts paper:

“Ultimately, we believe that investors will benefit from systematic rebalancing, but we don’t find a specific rebalancing threshold or frequency that consistently outperforms other forms of rebalancing. It may behoove investors not to stress about the specifics but rather to choose a rebalancing strategy they can comfortably stick with.”

– Vanguard

How to Choose Your Rebalancing Strategy

The most important thing is to have a rebalancing strategy and stick to it.

One final thing to think about is ways to rebalance in a more tax-efficient manner. There are five strategies to consider for this objective:

1. Focus on tax-advantaged accounts

Rebalancing within tax-advantaged accounts is tax-free. The Vanguard study I referenced found that applying this tactic increased after-tax returns by 44 basis points (or .44%) on an annualized basis without increasing risk exposure. So this one seems like a no-brainer.

Of course, this works best when you have a mix of asset classes in your tax-advantaged account.

2. When rebalancing taxable accounts, focus on targeting specific tax lots.

You can also primarily focus on shares with higher cost basis (in taxable accounts) or

3. Rebalance with portfolio cash flows.

Directing cash inflows such as lump-sum investments, dividends, interest into your portfolio’s underweighted asset classes is another way to help with rebalancing. This can also be accomplished with withdrawals such that you start by liquidating any overweighted asset classes first to generate cash to meet your lifestyle needs.

Most of our clients are either saving (accumulation phase of their life) or withdrawing (decumulation phase), so this type of rebalancing is an essential part of our methods to rebalance in a tax-efficient manner. It helps if the savings or withdrawals are predetermined, though, otherwise you fall into the trap of market timing that rebalancing is supposed to help avoid.

And for those that are retired but not spending down from their portfolio, at age 72 you are required to take RMDs from your IRA, so that is another opportunity to do so in the context of rebalancing in a manner that will be advantageous today and in the future from a tax perspective.

4. Rebalance within drift tolerance bands rather than back to target allocations.

This is effective for minimizing transaction costs and taxes. You opt to rebalance your portfolio partially to your target asset allocation. You can also focus more on asset classes that are extremely overweight or underweight to limit both taxes and transaction costs associated with rebalancing.

It can be difficult to quantify the trade-off between avoiding transaction costs and taxes and marginally approaching your target asset allocation, so it’s important to make rules-based decisions. It also helps to rebalance first with higher-cost basis shares to improve portfolio after-tax returns without increasing risk exposure.

5. Consider charitable giving

If you are charitably inclined, you can gift shares from your taxable accounts or take a qualified charitable distribution (QCD) from your traditional IRA(s) to rebalance while maximizing your tax benefits.

When gifting from non-retirement accounts, focus on low-cost-basis shares in lieu of gifting cash. Doing so means you won’t owe capital gains tax on any appreciation on the holding, because the taxable basis carries to the donee.

Get Your Questions Answered On The Show

Do you have a question you want answered? Submit your questions in the “Ask Me Anything” form at the bottom of my podcast page.

If you enjoy the show, you can subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts, and please leave me a review. I read every single one and appreciate you taking the time to let me know what you think.

Until next time, to long-term investing!

About the Podcast

Long term investing made simple. Most people enter the markets without understanding how to grow their wealth over the long term or clearly hit their financial goals. The Long Term Investor shows you how to proactively minimize taxes, hedge against rising inflation, and ride the waves of volatility with confidence.

Hosted by the advisor, Chief Investment Officer of Plancorp, and author of “Making Money Simple,” Peter Lazaroff shares practical advice on how to make smart investment decisions your future self with thank you for. A go-to source for top media outlets like CNBC, the Wall Street Journal, and CNN Money, Peter unpacks the clear, strategic, and calculated approach he uses to decisively manage over 5.5 billion in investments for clients at Plancorp.

Support the Show

Thank you for being a listener to The Long Term Investor Podcast. If you’d like to help spread the word and help other listeners find the show, please click here to leave a review.

Free Financial Assessment

Do you want to make smart decisions with your money? Discover your biggest opportunities in just a few questions with my Financial Wellness Assessment.