For more than three decades we’ve experienced an incredible bull market in bonds, but the current interest rate environment makes it unreasonable to expect similar returns going forward.

Low returns in any asset class have a funny way of leading to bad investment decisions. Although bonds have historically been considered the “boring” part of a portfolio, I view fixed income as an area of high risk when it comes to bad investor behavior.

Regardless of your near-term view on bond markets, there are four great reasons for a long term investor to buy bonds in 2017.

1. Returns may be low or even negative, but low volatility and diversification benefits remain.

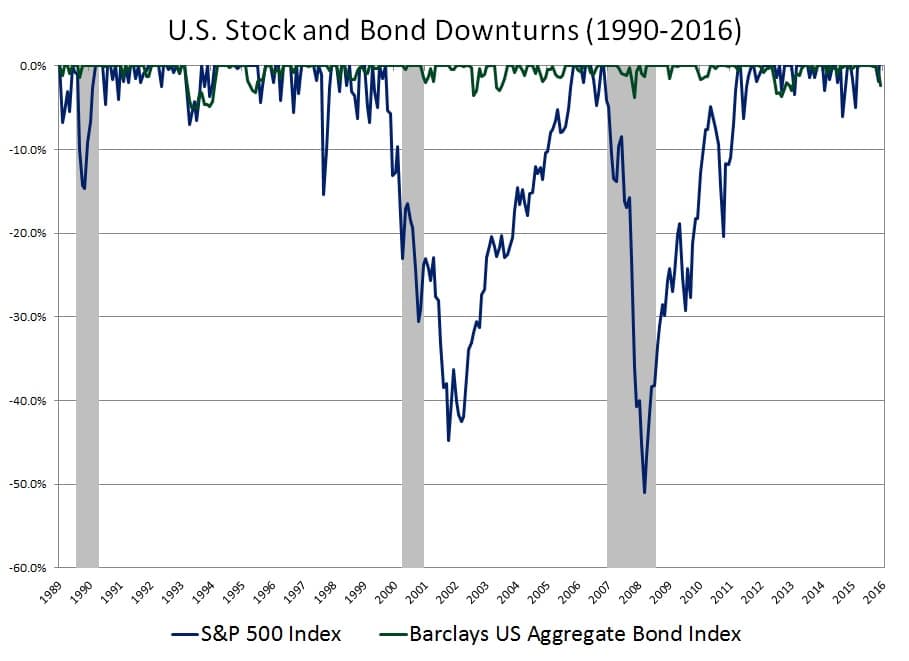

The primary purpose of your bond allocation is to decrease the volatility of your portfolio. Even if bonds experience temporary losses as interest rates rise, the worst bond market losses are not as severe as the worst stock market losses.

The chart below illustrates this point by comparing downturns on the S&P 500 (blue line) and the Barclays U.S Aggregate Bond Index (green line) since 1990.

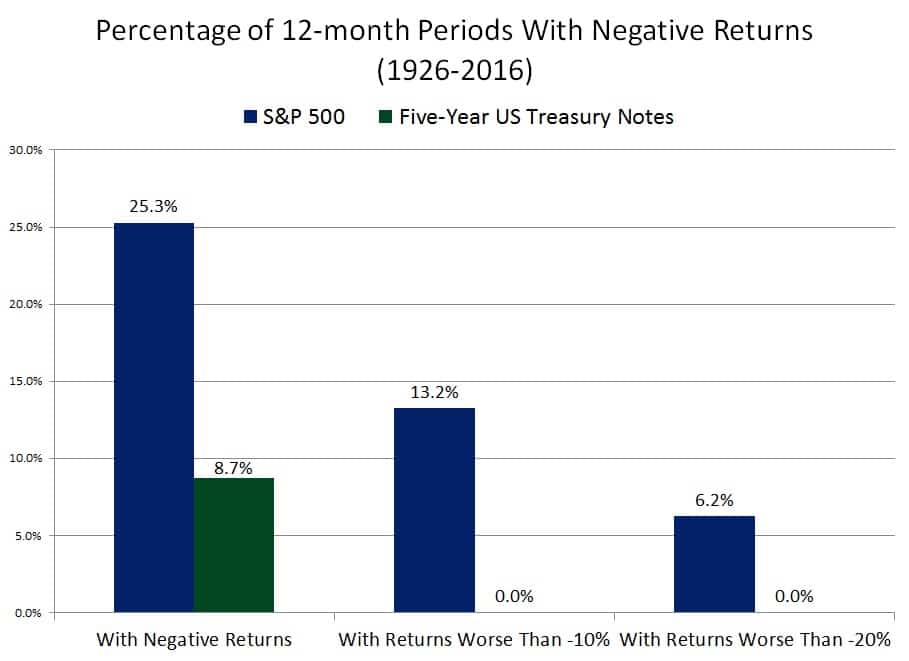

In order to take the data back even further, we can compare returns of the S&P 500 (blue bars) and Five-Year Treasury Notes (green bars) below.

Since 1926, bonds (green bars) had a negative return in only 8.7% of 12-month periods. Not once did bonds experience a 12-month period with losses worse than 10% or 20%. Compare those numbers to stocks (blue bars) and you can quickly understand the dramatic difference in the volatility between bonds and stocks.

When stock markets experience a sharp fall, bonds act as a diversifier and reduce the overall volatility of the portfolio. The relative lack of volatility is the primary reason investors should have fixed income exposure in their portfolios.

2. Rising interest rates are good for long-term investors.

Many investors fear a rising rate environment that results in declining bond prices, but long-term returns are actually enhanced by rising rates due to the ability to reinvest at higher rates.

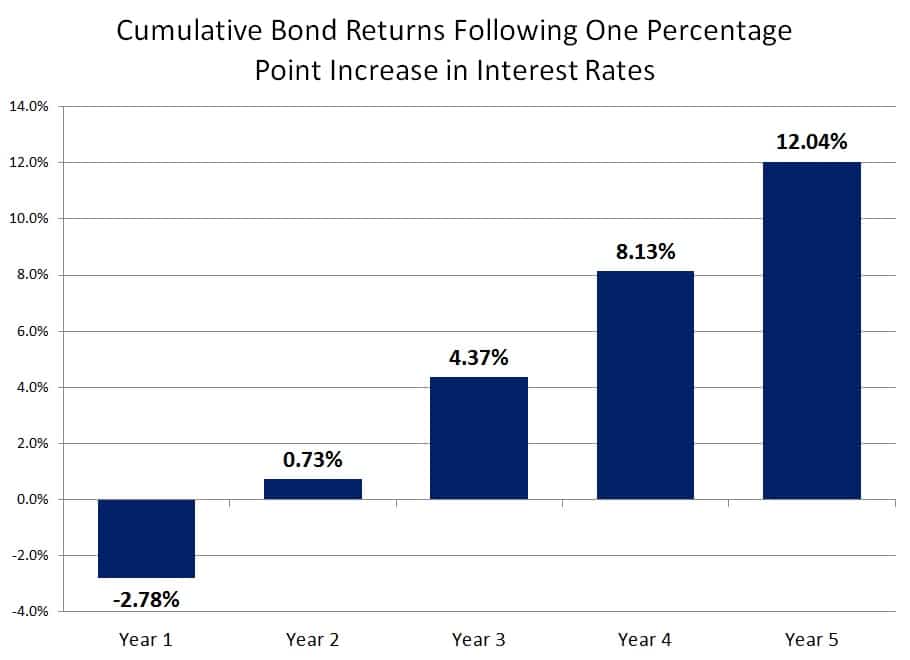

Consider the scenario below that depicts the impact of a one percentage point increase in yield on the cumulative total return for the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index, which has a yield of 2.61% and duration of 5.89 as of December 31, 2016.

As you can see, the one percentage point increase in interest rates results in a loss for Year 1, but by Year 2 the cumulative return turns positive because interest and principal are being reinvested at higher rates. Over time, the cumulative return grows even more as the benefit of higher rates compounds.

For ease of presentation, this analysis assumes a one-time parallel shift in yields and then no further fluctuation in interest rates. In addition, I assume that all income received is reinvested, which is extremely important because reinvesting income at higher rates helps offset the losses in the initial hike year and increases the total return of the bond portfolio over time.

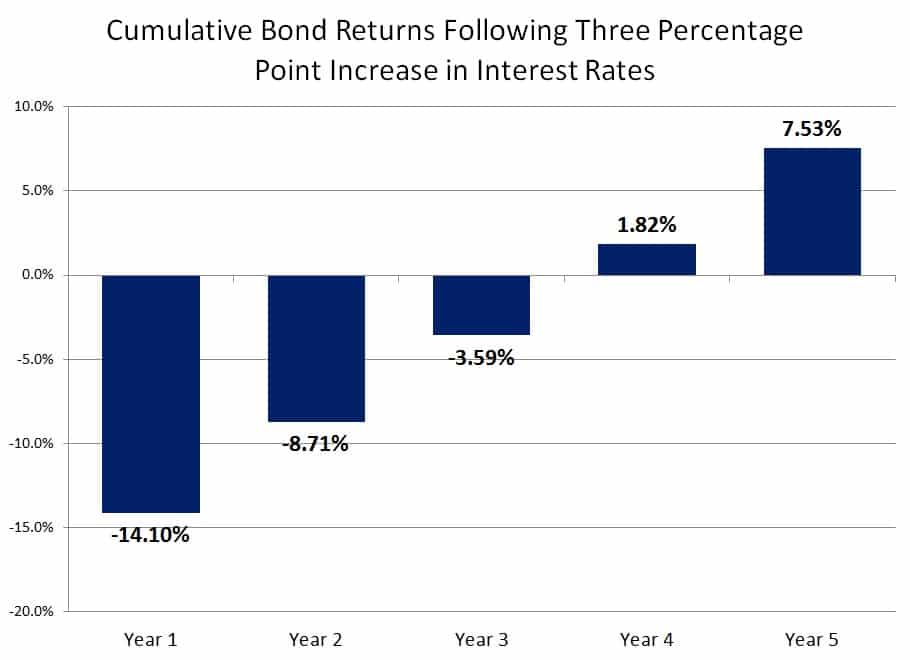

The same long-term benefits hold true for a more dramatic rate hike scenario of three percentage points, although recovering from the initial loss takes a little longer. An interest rate hike of this magnitude has occurred only twice in history (1980 and 1981), but serves as sort of a worst-case scenario analysis.

As you can see, the Year 1 return is dramatically worse with a larger interest rate increase – in fact, it would be the second worst 12-month return for the U.S. bond market ever. Although the initial loss is more dramatic compared to the one percentage point rate hike, the result is the same: higher yields benefit investors in the long run by providing higher returns over time.

3. Global exposure offers diversifying opportunities.

Investors shouldn’t limit themselves to just the U.S. bond market. Global bonds are the largest investable asset class, yet the area where most investors are underexposed.

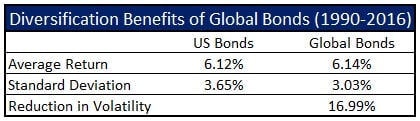

Using global bonds with hedged currency exposure has historically provided a dramatic reduction in volatility, which can be seen in the table below that compares the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index to the currency hedged Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index. The returns are very similar, but the standard deviation is nearly 17% lower for global bonds.

The biggest reason for the reduction in volatility is that each countries’ yield curve is shaped differently and the factors that impact change in yields are lowly correlated across countries. Another reason for the reduction in volatility is that global bonds add to the number of issuers in a portfolio and, thus, diversifies among different credit risks.

Making the safest part of your portfolio even less volatile is a no brainer. As a result, the opportunity to add global bond exposure is always a great reason to buy bonds.

4. Rebalancing to maintain the target risk exposure of your portfolio.

Investors that don’t rebalance periodically may end up with more or less risk than they are willing or able to tolerate. As a result, bonds are always an important part of a rebalancing strategy.

The beauty of rebalancing is that it removes our biases and emotions from investment decisions. When stock prices are down, the low volatility of your bond portfolio provides some dry powder to rebalance and buy stocks more cheaply.

When stock prices are up, buying fixed income helps bring the portfolio risk levels back in line with your financial plan.

Great perspective. I’m an individual investor who likes to play with portfolio construction. With respect to the Global Bonds recommendation, when I model un-hedged Global Bonds in my portfolio, it seems to result in a very slight increase to returns and to risk, and I assume the negligible impact is why you don’t recommend, and I would agree. Where do you get the return history for hedged Global Bonds? Many thanks!

Yeah, the currency exposure from unhedged global bonds give the asset class stock-like volatility and sort of defeats the purpose of their inclusion from an asset allocation perspective. I prefer currency-hedged fixed income exposure since I view fixed income purpose as lowering overall portfolio volatility – it sounds like you probably agree. The global bonds data I was reference are currency-hedged. I use Bloomberg and Morningstar Direct for index statistics, so not entirely sure where to direct you for free data. I know index providers share some free data. You may also look into FRED (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/).

Interesting piece. I was wondering what your take was on the strategies that, instead of having a permanent allocation both in stock and in bonds, allocate 100% to stocks if their momentum is positive, and 100% to bonds when it turns negative. Meb Faber and Gary Antonacci have popularised them. Some backtests are quite impressive, though they might depend on the time frame.

It always depends on a person’s situation. Generally speaking, I prefer building a long-term asset allocation that is built around a financial plan such that it accepts market declines rather than try to predict them via forecast or systematic process.

I just wonder why I should invest in bonds now, going through sure declines in the years to come, as your article shows. Why not keep your powder dry and invest it, after most of the decline is behind us?

My argument would be that you own them to offset the volatility of your stock portfolio. I’m also not a fan of investments based on predictions. People have been calling for bond losses for years. I’d expect they will have some bad years, but I’m not smart enough to know when those bad years will occur, nor am I concerned with the potential losses I might temporarily incur.

If you review historical interest rate since 1995, you will find that each year it seems that interest rate is sure to rise because the rate compared to the year before is almost always lower. The included chart shows the predicted interest rate and actual interest rate.

Especially in the last 7 years, people have been talking about an inevitable rising rate environment that is finally about to begin. Those people who have had their powder dry for the past 7 years missed out on the interest they could’ve earned in bonds.

If you have made a prediction based on public information, it is likely already incorporated into the bond prices. Meaning that if what you predict is true, the yield on current bond investments likely already is higher to compensate investors for the inevitable short term decline.

Would you advise a portfolio of individual bonds held to maturity or bond funds? Thank you.

In most circumstances, I prefer bond funds.

But bonds funds are subject to realized losses when bond prices fall and reach a stop-loss whereas individual bonds held t to maturity never face capital losses. Actually, bond funds are speculative trading vehicles that make bets on term-structure of interest rates.

I don’t agree, but my use of bond funds sounds very differently than yours. Not saying you are right or wrong, but we have very different objectives for that portion of the portfolio.

Why not a ladder of investment grade bonds held to maturity? Why bond funds?

These are my reasons: http://www.plancorp.com/individual-bonds-vs-bond-funds/

Some bond index funds emulate the same results from holding onto bonds until maturity and invest in longer dated bonds. It may not be an actual ladder where an equal amount is distributed to each maturity date but they achieve the same objective as a portfolio of individual bonds held to maturity.

You also get the added benefit of avoiding transaction costs, which are prohibitively high for individual muni or corporate bonds.

You prefer hedged funds for international exposure. Would you have the same views if your home currency was fairly volatile and variations had a rapid effect on inflation? And if your home currency tended to decline in a recession as everyone rushed to dollars?

(Yes, I am writing from UK and watching £ fall.)

I prefer currency-hedged global exposure because the volatility associated with currency exposure (no matter your home country) negates much of the benefits of foreign bond exposure. That said, I’m less educated about the non-US investor perspective, so it’s hard for me to answer your question with confidence.

Thanks. I respect both your taking time and your humility. My query probably is mainly relevant to UK and Australian investors.

would you say it’s better to have aggregate bonds of all durations for a long term B&H investor, to to concentrate on a certain duration (e.g. if you’re a long term investor short terms bonds might be a drag on performance). If so, is there a rule of thumb between the duration of the bonds and the time horizon of your placement?(so that you’ll end up with more in the end, even if interest rates hikes will make your investment temporarily go down)? thanks

There isn’t a one-size-fits-all answer, even if you classify yourself as a long-term, buy and hold investor. For example, you may agree that bonds are to reduce portfolio volatility, but do you want your bond allocation to emphasize low volatility in isolation or do you want the bond allocation to have the greatest volatility reduction impact on the overall portfolio. The answer to that question results in two different objectives for your bond portfolio and, thus, different “optimal” fixed income components/combinations.

Thanks. I guess the former scenario (reduce volatility in isolation) corresponds to cash or short-term bonds (thus producing a barbell portfolio of cash-like assets+stocks) whilst the latter corresponds to longer duration bonds (eg aggregate bonds)?

I was asking the question because I am from Europe, 10 yrs yields are close to zero for governement bonds here, and I saw there’s a good correlation between 10 yrs yields and the 10 yrs expected returns. So having cash or very short term bonds makes a lot more sense to me in all cases (with the possible exception that longer term bonds might go up during stocks drawdowns if I understand your message correctly).